BOOK REVIEW: The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory

Matthew Goldschmidt, Webster University – Saint Louis

Carol J. Adams writes with conviction of her vegetarianism and links it strongly with feminism as far back as the nineteenth century, citing well-known authors and using their works to illustrate her points that meat-eating is a violent act and that it not only oppresses, objectifies, and subjugates animals but also women. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory is about exposing the idea that to be a subject—to be a person—one has to eat meat. To eat meat is to make an object out of a subject, to take that which was living and consume it without giving a thought to the subject. Eating meat is the silencing of the subject and the silencing of the rights of the subject in order to make it palatable. In the process of making an object out of a subject, we deny the subject of life.

Adams begins with defining meat in the context of our culture. She gives examples of how our society thinks of meat with multiple texts stating that it is a virile food. By labeling meat as “virile”, which means that it pertains to an adult male or has the characteristics of a male, she makes the point that meat and meat-eating is seen as essentially male or masculine, leaving out any reference to the female or femininity (p. 26). She gives the definition of “meat” from The American Heritage Dictionary which states that meat is “the essence or primary part of something” (p. 36). To Adams, this definition, along with the assertion that meat is necessary in the meal, is patriarchy reasserting itself as dominant and reconfirming that what is masculine is what makes up the bulk of society and thus must be adhered to. This is in stark contrast to the definition of “vegetable” in our culture. Again, she uses The American Heritage Dictionary for the definition of vegetable: “suggesting or like a vegetable, as in passivity or dullness of existence, monotonous, inactive” (p. 36). To stress the idea that “vegetable” has been given a negative connotation she gives examples of various political figures being labeled as “vegetables” as a way of saying that they are unable to do anything or that they are lazy (p. 36). So, vegetarians are seen as going against patriarchal society by abstaining from that which makes a male masculine and in effect are labeled with feminine words such as “sissy” or “fruit” (p. 38) which reaffirms vegetarianism as feminine.

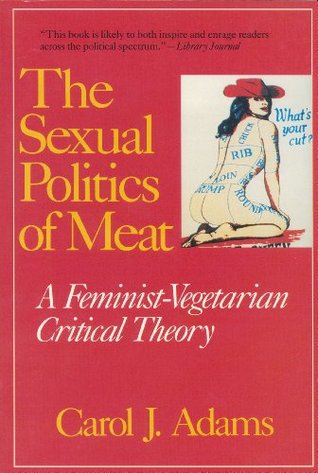

Adams proclaims that butchering is the main act that enables the eating of meat; labeling it as a literal dismemberment of the animal that will become a meal. This dismemberment and fragmentation of the animal allows people to separate themselves completely, body and mind, from the idea of the animal as a living, breathing creature which has been torn apart, dressed up, and placed in front of them. Through this separation, a change occurs which makes the animal become absent (p. 40). There can be no meat if the animal is still alive, so the presence of meat is in effect the representation of the death of an animal. This is an essential part of The Sexual Politics of Meat. The animal, now butchered and formed into something indistinguishable from what it once was, is made into an absent referent; that which is not present but is referred to. This extends from the literal absence of the animal into the way that animals who are killed and made into meat are talked about. The absence of the animal from the meal and from the minds of those who eat it is furthered by the names used to replace the animal such as “veal” from a murdered young cow; “pork”, “bacon”, “ham”, or “ribs” to refer to a slaughtered pig; and “steak”, “beef”, and “hamburger” for meat from a butchered cow (p. 47-8). The names of the meat are given based on parts from which they come. The animal is broken down into parts with each representing the whole yet destroying the literal whole and making the animal absent; the animal becomes a “thing” instead of a living being (p. 58).

This dismemberment and fragmentation of animals is mirrored in the fragmentation and dismemberment of a woman’s body into parts; rendering the female an absent referent. Women are broken down in patriarchal society by men, objectifying women and focusing only on specific parts such as legs, ass, breasts, vagina, and thighs. Through this observation it is evident that patriarchal society does objectify women and treats them as “things” instead of people. In referring to parts of a woman’s body, the woman is no longer seen as a woman in whole, but instead as parts that represent the whole whose wholeness is denied. The fragmenting and objectification of women is all too present in the world today. Adams draws attention to the sale and slaughter of female animals which is where most of the animal products we eat come from. This is true for the sex industry as well as the human trafficking industry where women make up the majority of the victims. Women are seen as body parts or as a means to an end, a way to satisfy the pleasure of the buyer the same way that animals are dressed up and presented to satisfy the needs of the meat eater.

Through phrases similar to “I feel like a piece of meat” women gain a vehicle for expressing the objectification, subjugation, and oppression they experience at the hands of patriarchal society. Many feminists have seized upon the metaphor of women being treated as meat or have identified themselves as feeling like a piece of meat. This reference to meat in such a negative way shows the violence by which animals are treated, processed, and dismembered in order to make them meat. Animals are judged by weight and the size of certain parts of their body, handled violently, crudely anesthetized and beaten, hung on racks, chained, have their k taken from them, and cruelly slaughtered at the hands of men. Adam posits that there is a hidden consequence to women taking up the phrase “I feel like a piece of meat” (p. 46). Using the imagery of butchering and the metaphor of women as pieces of meat, feminists reinforce the very same patriarchal structure that they oppose. The application of these ideas in feminism and feminist literature reinforce the idea of the literal fate of the animal in order to use the experience of the animal to illustrate the violations that they themselves have experienced.

In her book, Adams is concerned with ethical vegetarianism which is the result of the decision that eating meat exploits animals, as opposed to the current trend toward health-related vegetarianism which is only observed for health reasons. By stating this in her preface, Adams acknowledges those that she must fight for, those who are absent from the primarily health-conscious vegetarian arguments: animals. Choosing to focus on the absent animal is a critique of the health-conscious or faddish vegetarians. It is a critique not of what they do, but what they ultimately fail to acknowledge and, in the end, perpetuate: the oppression of women and the oppression of fellow animals. To this end, not only does a meat-eater silence the voices of women and animals, but so do the vegetarians who abstain from meat for purely health-related reasons.

The second half of The Sexual Politics of Meat focuses mainly on the use of novels and pamphlets to illustrate Adams’ point that vegetarianism is, and has been linked through time, with feminism. Citing Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and other pieces, she weaves together a somewhat discontinuous tale of women and men including vegetarianism in their works as a way to challenge male-dominated society and traditional gender roles. Although some works cited are nonfiction, most of what Adams writes on the combination of feminism and vegetarianism from the past is from what she gleans from reading between the lines of the actual text in novels. An argument can be made that the women and men who wrote these works only inserted such sparse lines into their texts in order to not draw attention to themselves from patriarchal society, but only to such an extent. The authors cited were already at the head of either vegetarianism or feminism in their time and so would not risk much in elaborating on the connection of both.

A topic worth mentioning, though Adams might not see it as such, is the glossing-over of the idea of animal rights. Adams sees fit to combine feminism with vegetarianism and give feminists a way of expressing their plight through that experienced by animals, but only in the last chapter does she give mention to animal rights other than the passing remarks she makes in regards to the rebuke of the idea of women’s rights seen in Thomas Taylor’s A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes. Adams can be seen expressing distaste and discomfort at the idea of using animals only as a means to an end in her criticism of feminists using phrases such as “I feel like a piece of meat” (p. 46), but not much in way of animal rights is discussed. Instead, it seems as though Adams places more emphasis on the aesthetic of killing and eating animals, using it as a rallying cry for fellow feminist vegetarians. However, missing from this work on the oppression, dismemberment and fragmentation of women is a commentary of actual substance on the devastating conditions imposed on animals that eventually culminate at the dinner plate. Instead of elaborating on the plight of the animal, she instead uses the animal as an extended metaphor for woman, leaving the reader with an unequal, lopsided view of the oppression of women and animals in patriarchal society.

The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory

Carol J. Adams (1990)

256 pp, Continuum Publishing Company, $13.94

© Copyright 2014 Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights. All rights reserved.

Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights is an academic journal that provides space for undergraduate students to explore human rights issues, challenge current actions and frameworks, and engage in problem-solving aimed at tackling some of the world’s most pressing issues. This open-access journal is available online at www.webster.edu/rightingwrongs.

Posted under:

Posted under: