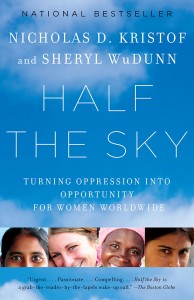

BOOK REVIEW: Half the Sky – Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide

by Angela Karas, Webster University – Saint Louis

Authors Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn explore the plight of women in Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, a book that observes the everyday lives of women and the difficulties they face. Across the world, women may hold different roles or are accustomed to different norms and ways of life depending on their cultures, but they are united in the fact that they are women. However, there is not an equal playing field when it comes to opportunities for women. Women in America compared to women in Iraq, Great Britain, or South Africa do not have similar experiences or prospects. Currently, women across the world are experiencing a dilemma: they do not have equal rights to men and they are taken advantage of mentally and physically. In many developing countries, they are utterly oppressed. The dangers of being an underprivileged woman in countries such as India, Thailand, Iran, or even the United States could mean rape, being sold into the sex trade, or not having permission to leave home without a male chaperone. Raising awareness of these human rights issues is only the beginning in a new age of advocacy, which aims to promote the rights of oppressed women and help them experience opportunity and a newer, more positive outlook on life.

Kristof and WuDunn interviewed women from around the world and used their stories to highlight the problem of gender inequality, which persists on a global scale. Many young girls, such as Srey Rath from Cambodia, do not have access to education and often get stuck in the villages they grew up in. In Rath’s case, she was sent to a bigger city to work and send money back home but ended up in a brothel, alone and penniless. Women in cultures with severe gender inequalities might be educated, but sometimes cannot work or even leave their home. Many of the women interviewed have been to hell and back, and they either reluctantly or openly told of their experiences. Meena from India, now in her thirties, shares her story of being kidnapped and trafficked as an eight-year-old girl. She was beaten and raped, and she eventually bore two children. She escaped her captors and later rescued her children from the brothel. Haunted and yet strong-willed from this whole experience, she has reinvented herself and improved the lives of her children.

Tales of these horrifying experiences in Half the Sky establish these testimonials as a platform for raising awareness. On their own, sheltered citizens of developed nations may not come to the conclusion that young girls are trafficked, or that countless numbers of women suffer from health concerns like fistulas or female genital cutting. Uneducated women are typically taken advantage of or not well cared for, and many are not fully aware of their human rights. The cultural differences highlighted in this book are also astounding; in a Western, individualistic culture, people typically do things for themselves. However, when women in collectivist cultures are told to work instead of go to school, they will do so for the good of their family or small community. Traditions are also passed down through the generations; mothers may sell their daughters into the slave trade, for instance, or encourage female genital cutting because they were exposed to it. It usually takes a nonconformist to point out the flaws in such practices or to encourage that new customs be made. In the book, the point is clear: Traditions do not have to be disgraced or uprooted, but if they cause harm or inflict pain, they must be changed.

The authors outline major solutions to help and encourage women. One way to counter the plight of women is to educate them. Education is a root solution when it comes to such human rights predicaments. Uneducated women are typically taken advantage of and may not even fully realize it. For example, Mukhtar Mai from Pakistan suffered from public humiliation and rape partly because she was poor and never attended school. Until she received the support she needed from her parents and local leaders, she felt helpless. Yet most of the time, uneducated and poor village women do not have a lot of connections. If they go missing or are trafficked, either no one will notice or the family does not have the ability or resources to find them. What Kristof and WuDunn point out is that educating young women and girls turns out to be extremely beneficial. Women are resourceful and smart and can contribute to better outcomes for their families, economically and socially. If they are given the opportunity to invest in education, they can learn different skill sets and gain the knowledge needed to open doors of possibility.

After outlining the goals that women themselves can attempt to accomplish, Kristof and WuDunn outlined some of the steps that the rest of the world can take to help. People worldwide must first acknowledge the setbacks and difficulties women face. Not only do people need to address these issues and bring them to light, but some sort of plan must be formulated to effectively introduce change. The first step offered is to develop coalitions between liberals and conservatives. Many people have differing viewpoints when it comes to contraceptives and the amount of funding that is offered for family planning, for example. However, both sides wish to improve the lives and status of women and girls. By taking hold of that common ground, more improvements can be made to facilitate actual change since there would be more cooperation and less hostility between groups.

Another international solution offered by the authors is to not “oversell” the issue. As with any polarizing topic, there are stereotypes associated with this problem. Many people hear the words “women’s rights” and already have preconceived notions as to what that might mean. Sadly, by expanding the issue too broadly, no one will have the drive or motivation to pursue the necessary changes. Instead of overselling the empowerment of women, Kristof and WuDunn favor taking an empirical and realistic attitude. The facts are startling enough to get people to help; if the position becomes too amplified, people become overwhelmed and do not see how their involvement will make a difference.

The final solution presented by the authors is to take men into account. As fathers, brothers, husbands, and friends to women, they are just as involved in this issue. They do not need to be blamed entirely for women’s oppression, but they do play a large role in continuing it. If women are truly going to be equal one day – and the authors note that women hold up half the sky, making up half the world population – men must take their role into consideration. This is a human rights dilemma, one not just affecting a single gender. On a side note, Kristof and WuDunn address American feminism and conclude it must not be so closed-minded. The empowerment of women in America is definitely different than empowerment of women in a developing country. Feminists must begin to invest in providing similar opportunities for all women regarding work, the family structure, and education. By offering awareness of global oppression and allocating resources to right organizations, women may be offered opportunities they never thought possible.

Kristof and WuDunn, for the most part, remain objective in their outlook on women’s rights issues. When criticizing or critiquing organizations and agencies that attempt to help women, they investigate both points of view. Emphasis is put on cooperation and balance among groups in order to achieve actual change. They approach the topic of women’s rights as people previously approached change regarding racial discrimination or environmental destruction. It all starts small; with awareness of the issues comes philanthropy, education, resources, and opportunities. Not wanting to limit these issues to women only, the authors label these human rights issues as humanitarian concerns – ones that transcend race, gender, or creed.

While the stories were heartfelt, well-researched, and aimed at moving people to act, the authors could have probably taken their own advice more. At times, Kristof and WuDunn did oversell the issue. Sometimes it is necessary to invoke change, but occasionally the book came across as condescending. The authors are so invested in this topic that sometimes they take the position that everyone who does not know enough about it is ignorant. While this passion is understandable, they should not come across this way. One other issue (which is a bit minor compared to the former) is that the book’s structure was sometimes disorganized. There were so many testimonials that needed to be covered, that sometimes two or three stories would intertwine in the same section. At times this made it slightly difficult to follow or completely devote time to one story. The only indication that the reader was approaching a new topic was the chapter headings or section captions. If these were not present, there were not a lot of transitions to clarify what material was being offered next.

Reading the testimonials from these women worldwide offered an important viewpoint into empowerment. There is no one better to speak with about this issue of oppression than the women who are directly affected by it. Perhaps never before have women’s rights been looked at from an empirical perspective; now solutions are not just based in theory, but they have realistic potential. The passion behind these stories is evident and gives an actual voice to men and women alike who are suffering and have no say in how to change their lives. They might be oppressed and powerless, but this is fuel to the fire of change. In a world where women are not always given a chance, this book is a step in the right direction. It advocates for women, empowerment, and opportunities for women who truly do hold up half the sky.

Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide

Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn (2010)

320 pp, Vintage, $15.95

© Copyright 2014 Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights. All rights reserved.

Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights is an academic journal that provides space for undergraduate students to explore human rights issues, challenge current actions and frameworks, and engage in problem-solving aimed at tackling some of the world’s most pressing issues. This open-access journal is available online at www.webster.edu/rightingwrongs.

Posted under:

Posted under: