BOOK REVIEW: Shake Hands with the Devil

by Melissa George, Webster University – Saint Louis

Over the course of 100 days, approximately 800,000 people lost their lives in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. This occurred in the small, landlocked African country despite the promise of “Never Again” echoed by the international community after the Holocaust. Lieutenant-General Romeo Dallaire commanded the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) during the three months of hell. In his book Shake Hands with the Devil, he recounts being ignored by the United Nations and Western countries throughout the crisis. He discusses the helplessness and depression he and his soldiers experienced, and why they were unable to prevent loss of life. This firsthand, heartbreaking account of the evil a society can inflict upon itself provides a window into one of the worst human rights events in modern human history. It demonstrates the fundamental flaws of the UN, the unwillingness of the world to help a country with no strategic value, and the complexity of genocide in the midst of civil war. Overall, Dallaire believes that the main reason UNAMIR failed was because of the inflexible UN Security Council, which refused to authorize intervention to stop the genocide.

Dallaire was shocked when he was appointed Lieutenant-General of the UNAMIR; he had no concrete knowledge or experience in Rwanda, to the point where he even questioned its geographic location. Nevertheless, he was thrilled about his new post and began learning as much as he could about the Arusha Peace Agreement he would be trying to enforce. The UN was not helpful in his efforts; it did not provide him with necessary intelligence regarding current events in Rwanda and its neighboring countries. Dallaire quickly drafted a plan, however, including a request for 5,500 troops. However, this was denied because the UN did not have the capacity or the will to approve the personnel. Few countries were ready to provide troops to a country with little resources or political power. This was the first of many frustrating experiences Dallaire encountered with the UN, yet he remained hopeful.

Throughout his mission, Dallaire and his team met with leaders from the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and the Rwandan Government Forces (RGF), which were associated with the current government, led by the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND). The rebels and the government seemed to support Arusha and bringing the country back together after years of conflict and human rights abuse. The main goal of the peace agreement was to set up an interim government encompassing all factions. However, meetings continued to deteriorate and the interim government was never sworn in. Compromise between the RPF, the MRND, and the RGF did not occur according to the set timeline. One of the problems UNAMIR faced was that the RGF did not have control over all of its troops. Many became rogue factions that supported extremist groups like the Interahamwe. This was a huge problem for Dallaire because it ruined most peace negotiations. The failure of installing a new government put UNAMIR at risk for missing all of its important peacekeeping deadlines.

As tensions grew, violence also rose. Several massacres took place that included child casualties. The first incident UNAMIR was sent to investigate was the murder of 21 people near the border of Ruhengeri. They discovered evidence (a glove) allegedly left behind by the RPF. However, Dallaire wondered if another force had committed the crime to frame the RPF and reduce their support. Shortly after this massacre, there was an attack on a village in northwestern Rwanda with an unknown number of Hutu victims. Then came a disturbing report that children had disappeared from a village near the Virunga Mountains. A few days later, soldiers found all but one of the children murdered. The lone survivor was taken to a hospital where she later died. Again, rumors were flying that the RPF committed the killings. UNAMIR was unsure on how to quell the violence, other than to continue to meet with the opposing forces and promote dialogue.

Dallaire met with an informant named Jean-Pierre, who was an officer in the Presidential Guard. In 1993, under the direct supervision of MRND head Mathieu Ngirumpastse, the informant began drilling young troops “under the guise of preparing a civil-guard-militia to fight the RPF if it resumed the offensive” (p. 142). In actuality, he and other commanders were training Interahamwe. These soldiers were ordered to create lists of Tutsis in their home communities. Jean-Pierre knew that the death squads he helped train “could kill a thousand Tutsis in Kigali within twenty minutes of receiving the order” (p. 142). The Interahamwe had several stockpiles of weapons ready for use. Jean-Pierre also warned of a plan to kill Belgian soldiers in hopes that the Belgian government would pull support for the mission. Dallaire sent this information to the UN in New York and its response floored him: His instructions were to not raid the stockpiles and not use force. Dallaire could not convince the UN otherwise, which is a failure that still haunts him. This demonstrated that the UN knew of the upcoming danger, yet did not take action to prevent the genocide.

Tensions increased and it became clear that both sides were preparing for war. The RPF had become isolated from the political process and negotiations. Arusha was on the brink of catastrophic failure. On April 6, Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira were assassinated when their plane was shot down. To this day it is not known who is responsible for their deaths. This event triggered the massive violence that was to become known as the Rwandan genocide. The phase of this plan was to assassinate moderate politicians, including the new leader of Rwanda, Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana. Extremist politicians went into hiding at this time, and roadblocks were set up by government forces and Interahamwe. Belgian peacekeeping soldiers were also detained, and ten were murdered despite Dallaire’s attempts to secure their release. Their deaths led to intended consequences; Belgium evacuated its remaining troops, and Western countries grew even less supportive of sending in more troops.

At this time, the UN began paying more attention to Rwanda and the mounting violence. Its troops were now being targeted. Yet it still did not authorize UNAMIR to use force, and it struggled to find another response that could stop the killing. The UN stated that it needed more information before it could do anything. France and Belgium, however, recognized the immediate danger posed to expatriates living in Rwanda; they moved in to evacuate Western citizens while leaving Rwandans begging for their help. Dallaire was furious because it felt that nobody cared about the Rwandan people. UNAMIR was receiving thousands of calls asking for protection as civilians were being slaughtered by the Interahamwe and other extremist groups, yet international forces evacuated Westerners and abandoned Rwanda.

The RPF was advancing on the RGF, adding the complexity of a civil war to the mess. There were simply not enough UNAMIR troops to help. They had to be strategically placed as Dallaire continued to fight for a ceasefire between the warring parties. The violence occurring was unimaginable. Civilians were being hacked to death by extremists groups with machetes, and the RPF was also committing murders and other abuses. Killers constantly violated peace agreements, as well as attacked buildings where people had sought refuge in the past – including churches, hospitals, and even UNAMIR’s headquarters. Violence continued as the RPF advanced to overtake Kigali and the international community debated if genocide was actually occurring. As the RPF won the battle at Kigali, extremists were pushed toward the border of Rwanda and Congo at Goma. This was when the United Nations, particularly the United States, decided to act by giving massive amounts of aid to the refugee camp. By late July, the genocide was over and Dallaire was sent back to Canada.

Dallaire’s haunting account of these three months of hell shows an important perspective missing from much discussion of the genocide today. He provides vivid details about the death he witnessed on a daily basis. The RPF is criticized for committing many abuses themselves; they were not passive victims. Tutsi rebels violated many UN agreements and also targeted civilians, while Hutu extremists murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians. Despite the blame that rests with Hutu forces, Dallaire also argues that the RPF was rigid in its stance toward peace negotiations and could have possibly lessened or prevented the violence. Dallaire’s account also highlights the catastrophic failure of the United Nations and the Western world. Throughout his mission, Dallaire struggled to get his troops food and water. He had to make requests for these items repeatedly. The book is very frustrating to read because of the constant breakdown between the UN and Dallaire’s forces on the ground. At times these accounts make the reader feel disgust and contempt toward the international community for its inaction and lack of human rights protection.

Shake Hands with the Devil is a horrifying account of the Rwandan genocide that needs to be shared and remembered. Dallaire’s book puts the reader in the midst of the fear and death that consumed Rwanda in 1994. It also educates us about the complexity of Rwanda’s political situation and the dynamics between extremist, moderate, and rebel groups. The world’s entire human rights framework is called into question. This book is a depressing, yet thought-provoking and important read. In order to understand how the world failed Rwanda in 1994, one must read Dallaire’s personal account.

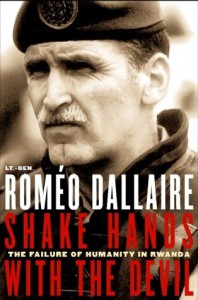

Shake Hands with the Devil

Roméo Dallaire (2004)

592 pp., Da Capo Press (reprint edition), $19.99

Editor’s note: Melissa George was one of seven Webster University undergraduates who traveled to Rwanda during the summer of 2013. This book review was written to complement that hybrid study abroad experience.

© Copyright 2013 Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights. All rights reserved.

Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights is an academic journal that provides space for undergraduate students to explore human rights issues, challenge current actions and frameworks, and engage in problem-solving aimed at tackling some of the world’s most pressing issues. This open-access journal is available online at www.webster.edu/rightingwrongs.

Posted under:

Posted under: