BOOK REVIEW: Left to Tell – Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust

by Brianna Willis, Webster University – Saint Louis

[download PDF]

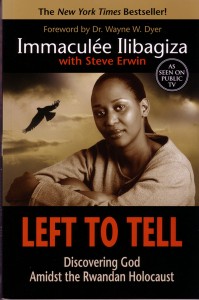

Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust by Immaculée Ilibagiza is a fascinating look into the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath through the lens of a religious woman. Ilibagiza is a Roman Catholic Tutsi who survived the 1994 Rwandan genocide by hiding for 91 days, along with seven other women, in a bathroom inside the home of a Hutu pastor. The room was 3 feet long and 4 feet wide. Ilibagiza lost her mother, father, and two brothers in the genocide; only she and her brother, who was studying in Senegal in 1994, survived. Today, Ilibagiza is a well-known public speaker who travels to colleges and spaces to talk about her experiences, which are outlined in three books. In addition to Left to Tell, Ilibagiza has also written Led by Faith: Rising from the Ashes of the Rwandan Genocide and Our Lady of Bideho: Mary Speaks to the World from the Heart of Africa. After the publication of her first book, she established the Left to Tell Charitable Fund (LTTCF) to help support Rwandan orphans. As a result of her work, Ilibagiza has met the Catholic Pope and her story is currently being turned into a movie.

After learning about Ilibagiza’s background, I’ll admit that I was pretty intrigued and excited to read her book. She sounded like an extraordinary human being who had been through so much. Left to Tell didn’t disappoint me; it was very well-written, and Ilibagiza uses powerful descriptions and tells stories that pull at your heart strings. She writes that “Rwanda is a tiny country set like a jewel in central Africa,” and “the forces of evil that would give birth to a holocaust that set my beloved country awash in a sea of blood were hidden from me as a child” (p. 3). When describing her time spent trapped in the small bathroom, she helps us understand the heart of her pain and anger while delving into her religious beliefs that helped her survive. Eventually, her faith would help her learn to forgive those who committed atrocities against her and her loved ones. She begins chapter 11 by writing: “I was deep in prayer when the killers came to search the house a second time” (page 91). She writes about her struggles to find peace and forgiveness through God, including her internal thoughts to God as murderers did their work outside the house. She admits some internal doubt she had while praying, which she calls “ugly whispers”. While she tries to ask God to protect her and the seven other women, these whispers tell her that prayers to God are useless lies. At the time, part of her wished death upon the killers and she harbored hatred in her heart. The “demons” in her head don’t just stop by calling out her hypocrisy; she also considers whether these weaknesses are why horrific things have happened to her and her family. She asks herself if, by hating the killers, whether she also hates God. Ilibagiza’s internal conflict created much emotion in me as I read this book, and while I studied the Rwandan genocide in general. How do you live amidst chaos, murder, and isolation, while also battling religious confusion in your own heart? In her epilogue, Ilibagiza states: “It’s impossible to predict how long it will take a broken heart to heal” (Ilibagiza, 205).

I found the book to be compelling and intriguing, but it left me with questions of my own. Can religion be a hindrance in times of crisis? The internal struggle Ilibagiza dealt with was fascinating to me, since the connection between religion and genocide was new to me when I read this book. Sometimes I found myself shaking my head because Ilibagiza sounded so lost and confused, and her religion wasn’t helping her even when she thought it was. It seems that the fact she survived the genocide only solidified Ilibagiza’s belief in God. The healing process she went through was also very faith-based, and perhaps her connections to the Church provided her with a structure and form for reconciliation that allowed for growth, peace, and forgiveness. At the same time, Ilibagiza’s religion during the genocide created not just positive feelings in her soul and mind, but negative ones that made her already horrific position even worse; these clashing emotions force us to think critically about the role of faith in survival. I would recommend Left to Tell to anyone who is spiritual and/or is interested in the study of religion – including those who don’t really understand God’s role in people’s lives. This is an excellent way to understand how someone’s religion can help them in times of need, even if that help is complicated.

Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust

Immaculée Ilibagiza (2007)

215 pp., Hay House, $14.95

Editor’s note: Brianna Willis was one of seven Webster University undergraduates who traveled to Rwanda during the summer of 2013. This book review was written to complement that hybrid study abroad experience.

© Copyright 2013 Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights. All rights reserved.

Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights is an academic journal that provides space for undergraduate students to explore human rights issues, challenge current actions and frameworks, and engage in problem-solving aimed at tackling some of the world’s most pressing issues. This open-access journal is available online at www.webster.edu/rightingwrongs.

Posted under:

Posted under: